Private Credit Part II

Private credit is booming...but is it a fortress or a mirage? Dive into the cautionary tales and hidden fragilities before the next collapse hits. Is your fund next?

Executive Summary

Our previous report, Shadow Banks & Private Markets (October 2024), exposed a seismic shift in financial activity away from traditional banking institutions and public markets toward the explosive growth of non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs).

This structural transformation, though seemingly promising, unveiled a dangerous vulnerability: significant liquidity risks arising from the inherently illiquid nature of private market investments.

Building boldly upon that unsettling revelation, this follow-up investigation plunges deeper, peeling back the layers to reveal what truly separates strong, resilient private credit funds from their precarious counterparts.

While private credit tempts investors with seductive yields, inflation-hedging properties, and tailored financing solutions, these alluring advantages mask profound risks beneath the surface.

Only through disciplined underwriting, rigorous liquidity management, expert leadership, and relentless risk control can these funds hope to withstand market turmoil.

Yet to genuinely understand strength, we must confront weakness head-on.

Through vivid, cautionary tales of spectacular failures—such as Archegos Capital Management’s catastrophic implosion, Medley Management’s Ponzi-like collapse, PeerStreet’s liquidity illusion, New Century Financial’s reckless subprime adventure, and Greensill Capital’s dangerous financial engineering—this report shines a glaring spotlight on the hidden pitfalls that brought these firms to ruin.

Excessive leverage, inadequate liquidity buffers, irresponsible underwriting, and toxic incentive structures emerge repeatedly as the silent assassins lurking within private credit.

Inspired by Charlie Munger’s timeless wisdom to "invert, always invert," we meticulously dissect these notorious collapses to extract crucial lessons.

In doing so, we construct a definitive roadmap—a comprehensive checklist—for investors, fund managers, and policymakers determined to build truly robust private credit vehicles.

But a few troubling questions loom large:

As capital continues to pour into private credit, are we on the brink of another cycle of hubris and devastation?

Is your private credit fund truly strong—or is it merely waiting to become the next cautionary tale?

Background

The private credit market offers numerous advantages for both borrowers and investors, making it an attractive alternative to traditional financing options.

For borrowers, particularly middle-market companies and private equity-backed firms, private credit provides access to capital that may not be readily available through banks or public debt markets.

This is especially beneficial in times of tightening credit conditions, as private lenders are often more flexible in structuring loans, offering customized financing solutions with tailored covenants and repayment terms.

Unlike traditional bank loans, private credit can also be deployed more quickly, enabling businesses to seize growth opportunities without the lengthy approval processes associated with institutional lending.

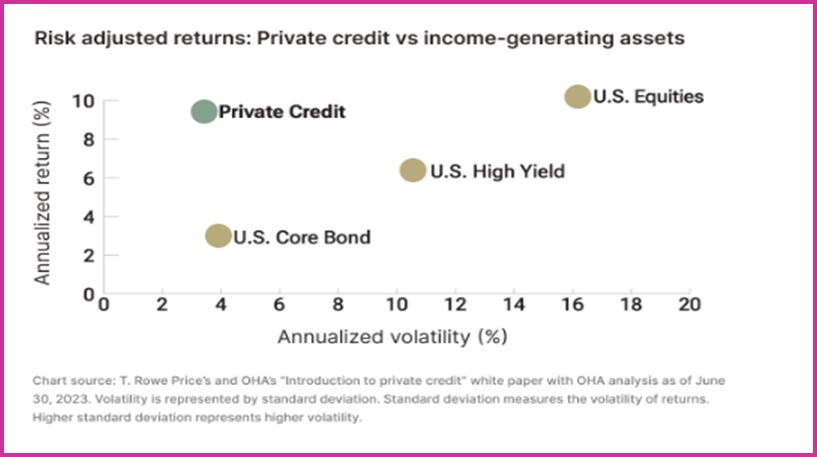

For investors, private credit presents an appealing risk-reward profile with relatively higher yields compared to public fixed-income securities.

Because private loans are often structured with floating interest rates, they can provide a hedge against inflation and rising rate environments.

Additionally, private credit investments are typically secured by collateral, reducing the risk of default and enhancing recovery potential in distressed scenarios.

The illiquid nature of private credit also contributes to an “illiquidity premium,” allowing investors to earn excess returns in exchange for holding assets over longer durations.

Another key benefit of private credit is its ability to provide portfolio diversification.

Unlike public markets, which are subject to daily price fluctuations and broader economic sentiment, private credit investments are less correlated with traditional equities and bonds, offering greater stability during periods of volatility.

Furthermore, the private credit market fosters direct relationships between lenders and borrowers, which enhances due diligence, monitoring, and risk mitigation.

As the market continues to grow, fueled by regulatory constraints on banks and increasing institutional demand for alternative investments, private credit remains a compelling asset class for those seeking strong risk-adjusted returns.

However, private credit investment also carries specific risks.

One of the primary risks is credit risk, as private loans are often extended to middle-market companies or leveraged borrowers that may have higher default probabilities than publicly traded firms.

Unlike public bonds, private credit loans are typically illiquid, meaning they cannot be easily sold in secondary markets, which can exacerbate losses if borrowers default.

Liquidity risk poses another significant concern.

Private credit funds often operate with long-term capital commitments, making it difficult for investors to exit their positions before maturity.

This lack of liquidity can pose challenges, particularly during financial crises when capital withdrawals may be restricted or subject to lengthy lock-up periods.

Additionally, private credit funds often use leverage to enhance returns, which can amplify losses if investments underperform or if credit markets tighten, increasing borrowing costs.

Operational risk is another factor, as private credit funds require strong due diligence and ongoing monitoring of portfolio companies.

Unlike public debt markets with standardized reporting and transparency, private lending relies on proprietary risk assessment, making fund managers' expertise crucial in evaluating borrower quality, structuring deals, and mitigating potential losses.

Finally, macroeconomic cyclicality and interest rate risks can significantly impact private credit portfolios.

A rising interest rate environment can lead to higher borrowing costs for leveraged companies, increasing the risk of defaults.

Conversely, a slowing economy can reduce business profitability, affecting cash flows and debt repayment capacity.

Given these risks, private credit funds must employ robust risk management strategies, including diversification, strong underwriting standards, and active borrower engagement, to navigate market uncertainties effectively.

The desirable characteristics of a strong private credit fund are clear and essential to achieving consistent, risk-adjusted returns across varying economic environments.

At its core, a robust fund maintains a well-diversified portfolio across multiple dimensions, including industries, borrower types, loan structures, and geographic regions.

Diversification mitigates concentration risk, reducing the impact of adverse events in any single sector or borrower category.

For example, a fund overly concentrated in cyclical industries, such as real estate or energy, may experience significant downturns during economic contractions, whereas one with a balanced mix of industries, including defensive sectors like healthcare or consumer staples, is more resilient during market turbulence.

Another essential characteristic of a strong private credit fund is disciplined underwriting and risk management.

Top-tier funds employ rigorous due diligence processes that assess not only the creditworthiness of borrowers but also macroeconomic trends, industry dynamics, and company-specific risk factors.

This comprehensive approach involves evaluating financial statements, stress-testing cash flows, analyzing leverage ratios, and scrutinizing collateral quality.

A strong fund ensures that loans are structured with robust covenants and protective clauses that safeguard investor capital.

These may include maintenance covenants, which require borrowers to maintain certain financial ratios, and senior-secured positions, which provide priority repayment in the event of default.

Liquidity management is another pillar of resilience.

Private credit funds often operate with varying levels of leverage, but excessive borrowing can amplify downside risks, especially in volatile market conditions.

A well-managed fund maintains a prudent leverage ratio that aligns with its risk profile, ensuring that it has sufficient liquidity buffers to manage unexpected borrower defaults or economic downturns.

This includes holding reserves for opportunistic lending during market dislocations, where credit spreads widen, and high-quality borrowers may need alternative financing sources.

An experienced and adept management team is a defining feature of a successful private credit fund.

Skilled fund managers possess deep industry expertise and a proven track record of navigating different credit cycles.

Their ability to assess risk, structure deals effectively, and respond proactively to economic shifts is crucial to long-term fund performance.

The best managers employ a proactive approach, actively monitoring portfolio companies and engaging with borrowers to mitigate risks before they escalate.

This hands-on involvement enables them to adjust loan terms, restructure distressed assets, and seize new investment opportunities when market conditions change.

Transparency and strong investor relations are also critical components of a resilient private credit fund.

Investors expect clear, regular reporting on fund performance, risk exposure, and underlying portfolio composition.

Funds that provide comprehensive disclosures, including performance attribution, default rates, recovery rates, and sectoral exposure, foster trust and long-term investor commitment.

A strong fund also clearly articulates its investment thesis and risk management strategy, ensuring that limited partners understand how capital is deployed and protected.

Moreover, adaptability is a crucial trait of top-performing private credit funds.

Economic environments and credit markets are constantly evolving, requiring funds to be agile in their approach.

A resilient fund capitalizes on market dislocations by deploying capital into undervalued opportunities while carefully managing downside risks.

For instance, in rising interest rate environments, floating-rate loan structures may become more attractive, providing better risk-adjusted returns.

Similarly, in periods of economic uncertainty, funds may shift toward senior-secured or asset-backed lending to ensure greater capital protection.

Finally, a strong private credit fund maintains a long-term investment philosophy focused on sustainable returns rather than short-term gains.

This involves aligning incentives between fund managers and investors, ensuring prudent risk-taking, and prioritizing capital preservation alongside yield generation.

Where it all Went Wrong: Some Case Studies

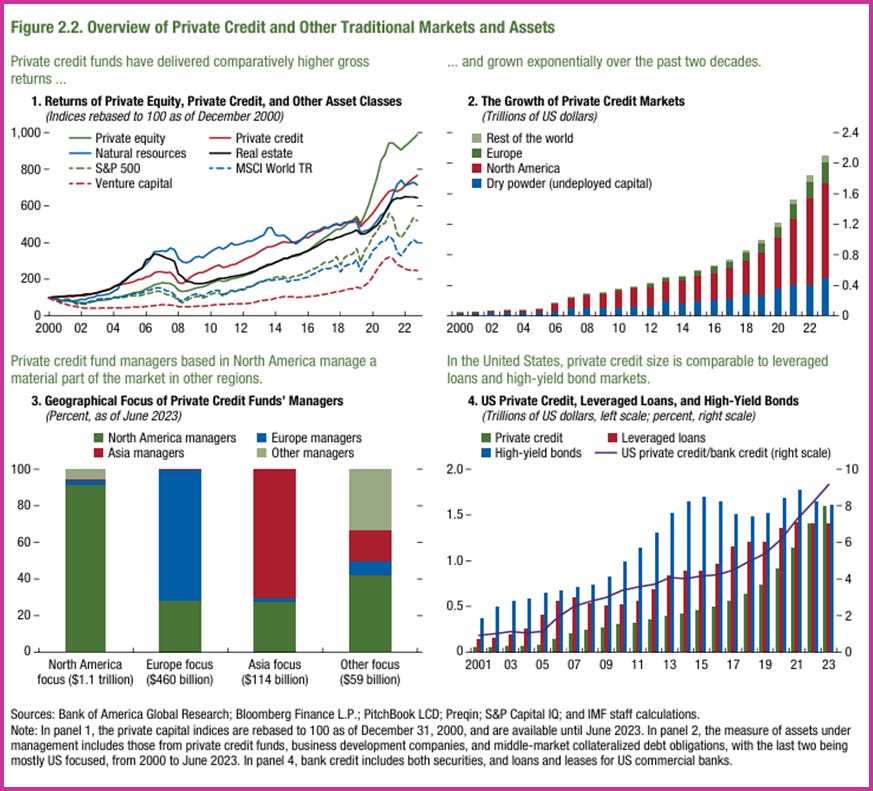

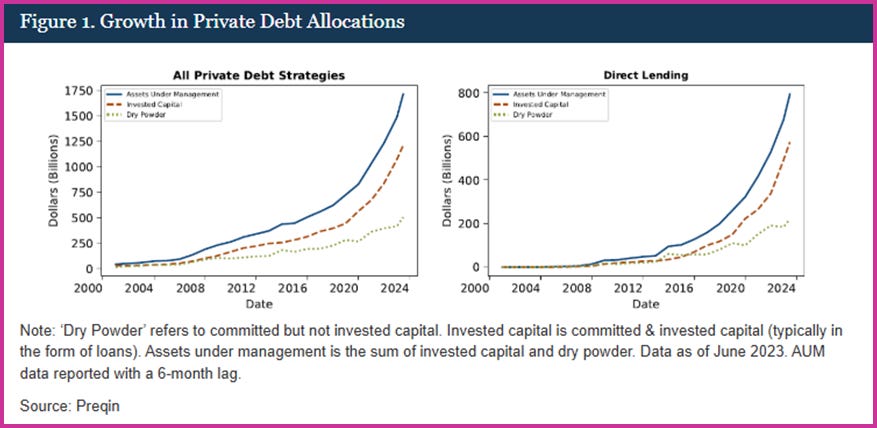

The growth of the private credit market over the past two decades has been extraordinary.

Of course, rapid growth usually leads to big problems at some point.

Using a lens of financial fragility and unintended consequences, failures in the private credit space are defined by excessive risk-taking, liquidity mismatches, and leverage.

The case studies that follow highlight recurring patterns of misallocated financial energy, where short-term gains were prioritized over long-term sustainability—until the underlying weaknesses became too large to ignore.

Archegos Capital Management: The Dangers of Excessive Leverage and Concentration

While not a traditional private credit fund, Archegos Capital Management operated with a structure and risk profile that mirrored many of the most dangerous attributes found in poorly governed private lending vehicles.

Founded by Bill Hwang—a former hedge fund manager previously banned from trading in Hong Kong due to insider trading charges—Archegos presented itself as a family office.

However, behind this façade, the firm engaged in aggressive, highly leveraged bets using opaque derivatives known as total return swaps.

Unlike direct equity ownership, total return swaps allowed Archegos to amass significant positions in a select few public companies—such as ViacomCBS, Discovery, and Baidu—without triggering disclosure requirements.

These swaps were arranged through multiple prime brokers, including Credit Suisse, Nomura, Morgan Stanley, and Goldman Sachs, none of whom had a complete view of Archegos’ overall exposures.

This fragmented setup created a dangerous illusion of stability.

By operating as a family office, Archegos avoided the regulatory scrutiny typically applied to hedge funds, enabling it to quietly accumulate over $100 billion in synthetic equity exposure backed by only $10 billion in actual capital—a staggering 10:1 leverage ratio.

The firm's downfall came swiftly in March 2021.

After ViacomCBS announced a $3 billion secondary stock offering, its share price plummeted.

Given Archegos' concentrated and highly leveraged positions, this decline triggered margin calls that Hwang was unable to meet.

Prime brokers began liquidating collateral at fire-sale prices, leading to a vicious cycle of forced selling that erased tens of billions of dollars in value almost overnight.

Credit Suisse alone reported losses exceeding $5.5 billion, prompting internal investigations, executive departures, and regulatory scrutiny.

As detailed in Reuters' coverage of the Archegos collapse, the incident blindsided global banks due to the opacity of the risks involved.

The total return swap structure allowed Archegos to bypass both regulatory transparency and market signaling mechanisms that would typically serve as early warnings.

Banks were lulled into complacency by Archegos’ family office status, wrongly assuming it posed minimal counterparty risk.

In reality, Hwang had quietly built a leveraged empire resting on a precarious foundation.

Archegos wasn’t merely an isolated implosion—it served as a stark warning.

A single entity, exploiting regulatory blind spots, nearly triggered a broader financial crisis by leveraging opacity and over-concentration.

This event exposed the vulnerability of even the largest global financial institutions to unforeseen risks lurking within the system.

Medley Management: A Private Credit "Ponzi Scheme" Unraveling

Medley Management, an alternative asset manager specializing in private credit, experienced a significant downfall due to a business model heavily reliant on continuous inflows of new investor capital rather than sustainable returns from its credit portfolio.

Operating multiple private credit vehicles, the firm aggressively raised capital to expand its lending operations. However, over time, underlying issues began to surface.

The firm faced allegations of inflating performance metrics and utilizing new capital to meet obligations to earlier investors, actions that bore resemblance to a Ponzi-like scheme within its private credit funds.

As fundraising efforts slowed and liquidity constraints intensified, Medley's financial structure became unsustainable, culminating in a Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing in March 2021.

This scenario exemplified a facade of stability maintained solely through continuous capital inflows; once that influx diminished, the entire structure unraveled.

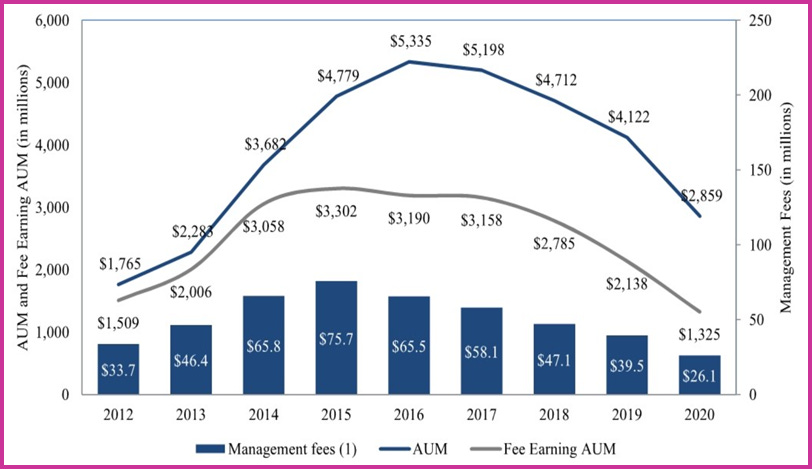

At its peak, Medley Management Inc. (MDLY) was recognized as a leader in private credit, managing over $5 billion in assets and serving as the external manager for two publicly traded business development companies (BDCs): Medley Capital Corporation (MCC) and Sierra Income Corporation (Sierra).

The firm marketed itself as a specialist in middle-market direct lending, promising investors stable returns while collecting substantial management fees.

Beneath this polished exterior, however, Medley engaged in practices marked by misaligned incentives, underperformance, excessive leverage, and self-dealing—factors that ultimately led to its collapse.

From its inception, Medley's strategy emphasized asset accumulation over investment performance.

The firm's revenue model was predominantly based on management fees linked to AUM, creating an incentive to focus on raising new capital rather than ensuring robust investment returns.

This approach thrived during periods of low interest rates and abundant capital, as investors sought higher yields in private credit markets.

Medley expanded aggressively, channeling funds into middle-market lending to companies often underserved by traditional banks.

However, as underwriting standards declined and investment performance lagged, cracks began to emerge.

By 2018, both MCC and Sierra underperformed relative to their peer BDCs, grappling with increasing loan defaults.

Facing underwhelming investment returns and diminishing investor confidence, Medley's executives attempted a controversial maneuver to sustain the firm—at the expense of shareholders.

In 2018, they proposed a three-way merger involving Medley Capital Corporation, Sierra Income Corporation, and Medley Management Inc.

This merger was presented as a strategy to create a larger, more diversified lending platform capable of achieving economies of scale and attracting institutional investors.

In reality, it was perceived as a bailout for Medley's insiders, particularly co-CEOs Brook and Seth Taube, enabling them to secure significant fees while consolidating underperforming assets into a more complex structure.

The proposal met with strong opposition from shareholders and analysts, who viewed it as a blatant attempt to protect Medley's management at the expense of retail investors.

Proxy advisory firms such as Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) and Glass Lewis recommended voting against the deal, citing concerns over corporate governance, excessive fees, and poor performance.

Legal actions ensued, alleging breaches of fiduciary duty, and by 2019, the merger was abandoned, inflicting severe damage on Medley's credibility.

The failed merger marked a turning point for Medley. Investor redemptions increased, and new capital became scarce, placing the firm in a precarious financial position.

The collapse of the merger also exposed the deteriorating quality of Medley's loan portfolios, previously obscured by aggressive accounting practices and dividend distributions that exceeded actual income.

Medley's stock price plummeted from over $17 per share in 2014 to less than $1 by 2020.

As revenues declined, the firm faced mounting legal challenges, escalating operational costs, and a shrinking AUM base.

With limited options, Medley Filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in March 2021.

The bankruptcy proved disastrous for investors, particularly those holding shares in Medley Capital Corporation and Sierra Income Corporation, who suffered significant losses.

The firm's collapse also served as a cautionary tale for the private credit market, highlighting the perils of prioritizing AUM growth over investment discipline.

Even as Medley teetered on the brink, insiders managed to extract substantial fees, underscoring the misaligned incentives prevalent in certain segments of private credit.

For years, the firm had promoted the promise of stable income and disciplined lending, only for investors to discover they had been supporting a fee-driven entity characterized by overpromising, underdelivering, and financial engineering.

Medley Management's downfall was neither accidental nor merely a stroke of bad luck.

It was a foreseeable consequence of a firm built on misaligned incentives, financial misrepresentation, and a blatant disregard for investor capital.

This case stands as a stark reminder that in private credit, illusory stability can persist for years, but once the inflow of new capital slows, the reckoning is both brutal and swift.

By the time Medley filed for bankruptcy, it had ceased to function as a genuine private credit manager.

Instead, it had devolved into a self-preservation vehicle for insiders, extracting fees while the firm deteriorated.

The lesson is clear: any private credit fund that prioritizes appearances over substance, fees over fiduciary duty, and complexity over transparency is destined to face a similar fate.

Ultimately, financial reality cannot be indefinitely deferred.

PeerStreet’s Fall: The Consequences of Mispriced Risk, Overexposure, and the Illusion of Permanent Liquidity

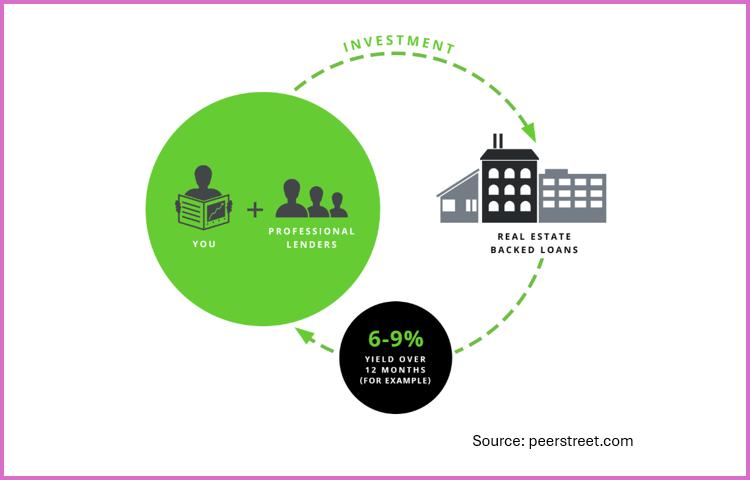

Peerstreet, once hailed as a fintech innovator in private real estate debt, set out with an ambitious mission: to democratize access to short-term, high-yield property loans by connecting accredited investors directly with real estate developers.

Founded in 2013, the company offered a compelling vision—stable returns, investments backed by tangible real estate assets, and exposure to a booming housing market that had long been the domain of banks and institutional players.

For years, the model appeared to deliver on that promise.

PeerStreet allowed investors to fund short-term real estate loans, typically 12 to 24 months in duration, secured by property and bundled into fractionalized portfolios.

These investment structures offered the appearance of diversification and safety.

Capital flowed freely from both retail and institutional investors, attracted by the platform’s promise of high yields and the perceived security of collateral-backed lending.

At its height, PeerStreet claimed to have originated over $1 billion in loans, propelled by low interest rates, surging housing demand, and a market-wide hunt for yield.

Yet beneath the sleek technology and polished pitch lay a fragile business model built on precarious assumptions.

PeerStreet’s continued operation was entirely dependent on a perpetual influx of capital and the uninterrupted turnover of its short-term loan book.

Like a treadmill, the business had to keep moving—new loans, new investors, new capital—or risk collapse.

The illusion of permanent liquidity, and the belief in an endless real estate upswing, were foundational. When either faltered, the entire structure was at risk.

That risk materialized in 2022, when the Federal Reserve, in a historic reversal of its ultra-loose monetary policy, began aggressively hiking interest rates to combat inflation.

The impact on the real estate market was swift and severe. Housing demand cooled. Refinancing pipelines dried up. Property values plateaued or declined.

The once-fertile environment for home flippers and developers deteriorated, and PeerStreet’s borrowers—many of whom relied on quick property sales or refinancing to repay their loans—began to default at growing rates.

As defaults climbed, institutional buyers who had been eager to purchase PeerStreet’s loan packages pulled back.

With no external buyers and limited capacity to absorb the distressed assets, PeerStreet was left holding a ballooning volume of non-performing loans.

Simultaneously, retail investors, spooked by delays in redemptions and mounting reports of defaults, began requesting withdrawals en masse—capital PeerStreet simply did not have.

The firm’s balance sheet had been built on the presumption of continuous liquidity and investor confidence.

With both evaporating, it entered a classic liquidity spiral. Redemptions stalled, panic spread, and PeerStreet’s ability to meet its obligations crumbled.

By mid-2023, the company’s situation was untenable.

With capital inflows frozen, its loan book underperforming, and investor faith shattered, PeerStreet filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on June 26, 2023.

The collapse exposed the deep flaws in PeerStreet’s model: its over-reliance on a single asset class, its mispricing of risk, and its assumption that liquidity would always be available.

Real estate-backed loans, marketed as safe and collateralized, had become liabilities in a contracting market.

PeerStreet’s failure was not simply the product of an unfortunate market cycle—it was the predictable outcome of a business built on unstable foundations, optimistic assumptions, and a fatal underestimation of the financial system’s cyclical nature.

PeerStreet’s failure is not merely a tale of unfortunate timing; it is a textbook example of structural fragility, overexposure, and the dangers of mispriced risk.

The firm’s collapse delivers several enduring lessons for investors and market participants alike.

First, liquidity is not a permanent feature of any financial system—it is a byproduct of confidence.

When investor sentiment shifts, platforms that depend on uninterrupted capital inflows can unravel almost overnight.

Second, the cyclical nature of markets cannot be ignored. PeerStreet built its business on the assumption that property values would continue to rise and that refinancing demand would remain stable—assumptions that proved disastrously fragile when market conditions reversed.

Lastly, the mispricing of risk can be fatal.

PeerStreet extended credit to borrowers who lacked the financial resilience to withstand a downturn, underwrote loans aggressively, and failed to prepare for adverse scenarios.

The result was not just a business failure, but a powerful reminder of the consequences of building a financial model on misplaced confidence and unsound risk assumptions.

In the end, PeerStreet didn’t collapse because real estate was inherently risky.

It collapsed because it built an entire business model on the assumption that real estate would never be risky again.

New Century Financial: The Subprime Private Credit Bubble

New Century Financial was once one of the most aggressive and prominent players in the booming world of subprime mortgage lending.

Founded in 1995, the firm rose rapidly to become one of the largest private subprime originators in the United States, targeting borrowers with poor credit histories and unstable financial backgrounds.

Its meteoric growth was fueled by a housing market in overdrive—home prices climbing year after year, a deep pool of eager borrowers, and an industry eager to feed the securitization machine.

The company's business model was built on a dangerously flawed foundation: the belief that home prices would rise indefinitely. This assumption masked a fragile and unsustainable lending structure.

New Century eagerly originated loans to high-risk borrowers under the assumption that appreciation in real estate would provide a built-in cushion—allowing borrowers to refinance or sell before defaulting.

The firm’s underwriting standards deteriorated as it competed for market share, issuing “low-doc” and “no-doc” mortgages that required little to no verification of income or assets.

Many of these loans came with adjustable rates that reset to unaffordable levels within a few years, setting up borrowers for inevitable financial stress.

New Century’s business was immensely profitable in the short term.

It collected fees from originating mortgages, quickly bundled the loans into mortgage-backed securities, and sold them to institutional investors.

These MBS products were pitched as safe investments, backed by tangible real estate collateral and the illusion of perpetual home value appreciation.

With every securitization cycle, New Century recycled the proceeds into more loans, amplifying leverage and embedding systemic risk deeper into the financial ecosystem.

By 2006, cracks in the housing market began to show.

Interest rates rose, home prices plateaued, and refinancing pipelines started to close.

Borrowers with subprime adjustable-rate mortgages began to default in growing numbers as their payments reset.

The value of mortgage-backed securities began to fall, and the demand from investors dried up.

New Century, once flush with capital, found itself holding a ballooning portfolio of toxic loans it could no longer sell.

As delinquencies soared, the firm faced a mounting liquidity crisis.

Credit markets began to freeze, and banks, wary of exposure, stopped lending to mortgage originators altogether.

Without the ability to roll over debt or offload its loan inventory, New Century’s financial position deteriorated rapidly.

In February 2007, the company announced it would be forced to write down a large portion of its loan book—an admission that triggered a collapse in investor confidence.

Its stock lost over 90% of its value in mere weeks.

By March 2007, the company was in freefall.

It missed debt obligations, lost warehouse lines of credit, and saw its reputation evaporate.

In early April, New Century Financial filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Shareholders, employees, and institutional investors were left holding near-worthless positions.

The company’s failure exposed billions in bad loans and toxic securities and stood as one of the earliest and most visible warnings that the subprime bubble was not just overinflated—it was already bursting.

As more capital floods into private credit chasing yield, it’s tempting to believe today’s risks are better understood than those of past cycles. But are they?

What truly separates a resilient private credit fund from one destined to unravel when the tide turns?

(This is a professional-level report for industry professionals. Please upgrade to Santiago Capital Pro to continue…)