National Interest & Deglobalization

The New Investment Paradigm

Executive Summary

There are moments in history when the ground beneath markets shifts so profoundly that yesterday’s assumptions become tomorrow’s blind spots.

For nearly half a century, investors lived in the age of globalization, where efficiency reigned supreme.

Outsourcing to low-cost economies, fine-tuning “just-in-time” supply chains, and expanding multinational footprints across borders were accepted as unquestionable laws of value creation.

That era is ending.

The consensus that once bound the global economy is splintering under the weight of escalating U.S.–China trade tensions, resurgent nationalism, and the urgent reshoring of critical industries.

The very fabric of globalization is fraying, replaced by an era of systemic upheaval, geopolitical rivalry, and economic fragmentation.

In short, a “Fourth Turning” has arrived, one that will reshape the investment landscape for decades to come.

For investors, the message could not be clearer: the assumptions of the old order no longer apply.

Globalization once allowed capital to chase efficiency, squeezing profits from cheap labor and seamless supply lines.

That model has collapsed. Efficiency has given way to fragility, while resilience has become the premium asset.

Political leaders, chastened by pandemic shortages, semiconductor scarcities, and the weaponization of energy supplies, now prioritize security and redundancy even at the cost of higher prices.

This inversion creates both peril and promise.

Firms that once flourished under the gospel of global efficiency may find their advantages eroding.

At the same time, companies positioned in strategic industries tied to national security stand to receive subsidies, preferential contracts, and regulatory protection.

Even the capital markets themselves may fragment along geopolitical lines, forcing investors to rethink diversification strategies that once seemed prudent.

As such, thinking differently is no longer optional. Geopolitics must now sit at the center of portfolio construction.

Multinationals that once thrived in a borderless world may face systemic headwinds as governments restrict flows of capital, technology, and talent.

In contrast, “national champions” aligned with state priorities in defense, energy, semiconductors, and critical minerals will gain structural advantages that extend beyond traditional financial metrics.

The investment lens must shift: supply chain resilience, regulatory adaptability, and alignment with national priorities are now as vital as balance sheets and earnings growth.

The fracture of global systems into rival blocs will only intensify the challenge.

One sphere is coalescing around the United States and its allies, another around China and its partners.

Exposure to one bloc may heighten risks in the other, demanding a regionally tailored approach to investing that rejects the illusion of a seamless global marketplace.

Opportunities are also diverging sharply from those of the past era.

Strategic industries such as semiconductors, artificial intelligence, defense, cybersecurity, energy independence, and pharmaceuticals are being reclassified as pillars of national survival.

Governments are pouring billions into reshoring production, hardening supply chains, and securing domestic capabilities.

Infrastructure, whether in logistics, renewable energy grids, nuclear power, or rare earth refining, will represent another durable growth theme.

Regional trade blocs such as USMCA in North America or the European Union’s push for strategic autonomy will create localized winners.

By contrast, industries tethered to fragile supply chains or exposed to sanctions, tariffs, or export restrictions may face structural decline.

History confirms the pattern. When national interest takes precedence, markets are remade.

Britain’s naval and industrial policies during the Napoleonic Wars fueled fortunes in textiles, steel, and shipbuilding.

The United States, in the aftermath of the Civil War, embraced tariffs and massive railroad investment to accelerate industrialization. World War I and the interwar collapse of trade forced investors toward domestic steel, chemicals, and energy.

World War II and the Cold War transformed defense and aerospace into permanent growth sectors. The oil crises of the 1970s exposed the perils of foreign dependence and sparked waves of investment in domestic energy and alternative technologies.

Each moment reinforced the same lesson: when nations demand security and self-sufficiency, capital flows to industries that deliver it.

The outlook today echoes these precedents.

We are entering a new age of state-driven capitalism, where governments reclaim a commanding role in shaping economic outcomes.

The disinflationary tailwinds of globalization have given way to structurally higher costs, inflationary pressures, and persistent geopolitical risks. Yet within this turbulence lie extraordinary opportunities.

Those who align with resilience, redundancy, and national priorities will find themselves in the slipstream of policy and power, while those who cling to the assumptions of the old order will fade into irrelevance.

Readers may notice that the themes in this paper echo arguments we have made in earlier reports.

That is not by accident. It is in fact by design.

We continue to return to this subject because it remains the most important issue facing investors today.

Repetition reinforces significance, and with each new discussion we aim to provide additional layers of insight, more detailed analysis, and a sharper understanding of how these forces will shape the decades ahead.

This is no ordinary transition. It is a generational reordering. Capital allocation has become an exercise not only in reading market signals but in navigating the crosscurrents of power, policy, and national interest in a fractured world.

The question is no longer whether investors will adapt, but how quickly they recognize that the rules of the game itself have changed.

Background

For nearly half a century, investors operated inside a framework that appeared unshakable: Globalization.

Market liberalization was not just policy but ideology, international cooperation was celebrated as progress, and the pursuit of efficiency was treated as an almost moral imperative.

For a generation of business leaders and policymakers, globalization was not one option among many; it was the only path forward, the defining force that shaped how economies, corporations, and capital itself were expected to behave.

The collapse of the Soviet Union seemed to validate this worldview, opening vast new markets to Western capital.

China’s entry into the World Trade Organization cemented the belief that even geopolitical rivals could be brought into the fold of an integrated global system.

Trade agreements multiplied, supply chains lengthened, and technology knit the world closer together.

Investors came to see borders not as obstacles but as opportunities.

Capital moved with astonishing ease, multinational corporations flourished, and supply chains stretched across continents with precision and speed.

The environment this created was not only profitable but predictable.

Efficiency gains appeared inexhaustible, each new wave of offshoring promising still lower costs.

Disinflation was treated as a permanent tailwind, delivering both stable prices for consumers and expanding margins for corporations. Central banks, freed from inflationary pressure, kept rates low, fueling a golden age of rising valuations.

For investors, geopolitics was not ignored so much as dismissed, relegated to background noise. Wars, rivalries, and political disputes seemed to matter less than the inexorable tide of trade and finance binding the world together.

That confidence has now unraveled.

The accelerating trade conflict between the United States and China has forced the recognition that economics and politics cannot be separated.

The same supply chains once held up as marvels of efficiency are now seen as liabilities, vulnerable to disruption and manipulation.

Commodities, long considered neutral building blocks of commerce, are openly politicized, turned into instruments of leverage.

Governments that once championed unfettered globalization are rediscovering the rhetoric of “national champions,” elevating certain firms and industries into tools of strategy and survival.

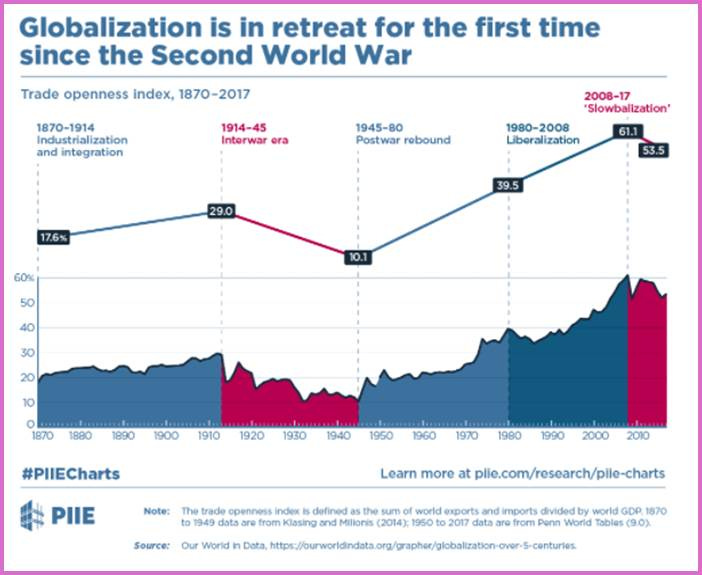

For the first time since the Second World War, globalization is not advancing but reversing, its underlying logic collapsing in real time.

In this new environment, the watchwords are no longer efficiency and integration but sovereignty, resilience, and self-sufficiency. Governments are deliberately trading cost for security, redundancy for optimization, and control for openness.

This represents more than turbulence in an otherwise stable system. It is a structural realignment that is reshaping the architecture of the global economy itself.

History reminds us that such reversals are not unprecedented. The late nineteenth century saw the optimism of free trade give way to waves of tariff protection as nations sought to shelter their industries from competition.

The interwar years delivered an even starker lesson: global trade collapsed, capital flows reversed, and governments turned inward, forcing investors to focus on domestic industries like steel, energy, and chemicals.

In each case, the confidence of the previous era proved fleeting, and those who assumed the old order would endure were caught unprepared.

For today’s investors, the warning is clear.

Strategies built on the assumptions of globalization—confidence in neutral supply chains, faith in the apolitical nature of commodities, trust that capital could always move freely—are being dismantled.

National interest, not global efficiency, has become the organizing principle of economics and finance.

To miss this transition is to misread not only the moment but the forces that will define investment returns for decades ahead.