Borders Before Balance Sheets

When National Iterest overtakes Economic Interest

Executive Summary

It always starts with a line in the sand.

A new administration enters with flags waving, fists clenched, and promises of strength. But strength, it turns out, is a slippery thing. Is it measured in GDP? In military power? In the willingness to let markets bleed so that borders can be fortified?

The world has a long memory for these moments. Maps redrawn. Alliances tested. Economies contorted in service of something greater—or darker—than profit. When national interest overtakes economic logic, the terrain shifts beneath everyone’s feet.

Sometimes, it leads to prosperity. Sometimes, to ruin. More often than not, it leads to unpredictability. The kind that doesn’t show up in balance sheets until it’s too late.

We’ve seen this movie before. Protectionism rarely walks alone—it drags along inflation, retaliation, and uncertainty.

And when global markets are priced as if nothing could ever go wrong, those frictions become accelerants. Momentum stalls. Assumptions crack. Complexity rushes in.

What happens when entire industries are selectively shielded or sacrificed? When capital is no longer free to flow, but herded by policy and constraint? When the playbook changes mid-game and the referees write new rules with each passing month?

This isn't theoretical. It’s happening again—right now. Quietly in some corners. Loudly in others. The rhetoric of self-reliance has already outpaced the economics of efficiency. And the political appetite for compromise is running dangerously low.

Tariffs, trade wars, and the slow disintegration of globalization’s promises are no longer fringe scenarios. They’re being formalized, justified, and celebrated. Voters are being asked—implicitly or not—to endure pain now for an undefined payoff later.

That bargain has a history. And history rarely rhymes with mercy.

The implications ripple far beyond trade balances or GDP projections.

They reach into inflation, valuation models, global capital flows, and the very definition of strategic advantage.

They distort incentives, challenge alliances, and rewire the foundations upon which the modern investor has built expectations.

What emerges when national interest takes the wheel is not chaos. It’s something more dangerous: a new order whose rules are still being written.

And if you're wondering where this road leads, you’re asking the wrong question. The real question is: who gets run off the road first?

Background

Throughout history, nations have repeatedly made decisions in which the pursuit of national interest—defined by political, strategic, or cultural imperatives—has taken precedence over economic gains.

These decisions reflect a complex and often fraught interplay between sovereignty, security, ideology, and a country’s broader vision for its role in the global order.

Frequently, such choices involve the deliberate sacrifice of immediate economic benefits in order to achieve goals deemed vital to long-term stability or strategic advantage.

What follows are detailed examples illustrating this dynamic across domains as varied as geopolitics, trade, and defense.

Sanctions and Economic Isolation

Few actions highlight the tension between political goals and economic consequences as clearly as economic sanctions.

They represent one of the most prominent and deliberate ways in which nations subordinate economic gains to national interest.

The United States’ sanctions on countries like Iran, North Korea, and Russia offer clear illustrations of this approach, where political imperatives overshadow even significant economic fallout.

Sanctions against Iran, for instance, were implemented to curtail its nuclear ambitions and limit its growing influence across the Middle East.

While these measures were designed with security in mind, their ripple effects extended to U.S. allies and multinational companies.

European countries, particularly Germany and France, faced substantial economic setbacks as firms were forced to exit lucrative contracts and abandon opportunities due to U.S. pressure.

Corporations like Airbus and Total forfeited multi-billion-dollar deals, and energy markets absorbed new waves of uncertainty.

Despite the costs, the U.S. government maintained that confronting Iran’s geopolitical ambitions was essential for both American and global security.

A parallel example emerged in 2014, following Russia’s annexation of Crimea. Sanctions were swiftly imposed with the intent of deterring further aggression.

These measures not only disrupted global energy markets but also curtailed access to Russia’s natural resources, inflicting economic damage on both Russia and its trading partners.

European nations—many of which relied heavily on Russian energy exports—suffered particularly sharp consequences during periods of elevated gas prices.

Still, NATO countries broadly endorsed the sanctions, viewing them as a necessary cost to uphold European security and counter violations of territorial sovereignty.

Sovereignty and Self-Determination: Brexit

The United Kingdom’s decision to exit the European Union provides a powerful modern example of national interest superseding economic logic.

Membership in the EU offered Britain numerous economic advantages: access to the world’s largest single market, tariff-free trade, and an influential seat within a major economic bloc.

Yet in the 2016 referendum, those benefits proved insufficient to outweigh concerns over national sovereignty, immigration policy, and cultural identity.

Supporters of Brexit argued that reclaiming full control over domestic laws, trade agreements, and border security was more important than the financial and commercial risks of departure.

The consequences were immediate and profound: disrupted supply chains, reduced trade volumes, and the relocation of major financial services firms to other EU jurisdictions.

Nonetheless, for a sizable portion of the electorate—and for many political leaders—the principle of self-determination justified the economic upheaval.

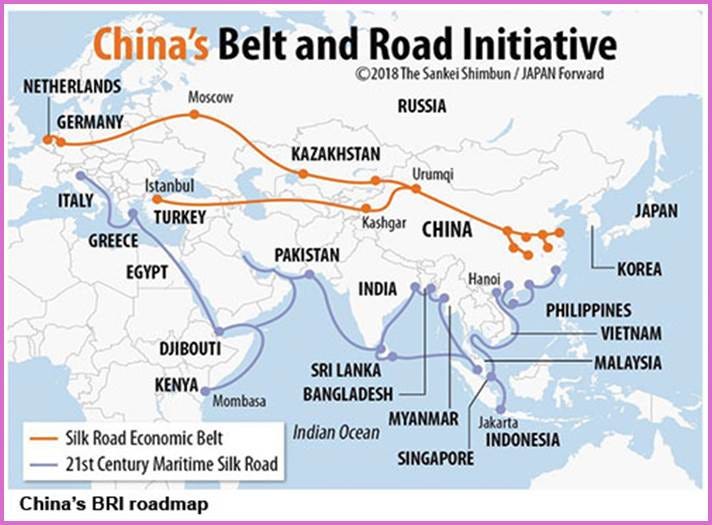

Strategic Investments: China’s Belt and Road Initiative

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, provides a distinct case of national strategic priorities overriding traditional economic return metrics.

Intended to foster global trade and infrastructure development by connecting Asia, Europe, and Africa, the BRI is ambitious in scale—but not necessarily in efficiency.

Many BRI projects have been undertaken in unstable or high-risk regions, where the prospects for profitable return are uncertain at best.

One high-profile example is the Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, which became financially unsustainable and was ultimately leased to China for 99 years.

From a narrow economic standpoint, such outcomes might appear wasteful. But China’s calculus is different.

These investments serve a broader purpose: expanding geopolitical influence, securing long-term access to strategic resources, and building dependencies that reinforce China’s leadership in the global system.

The inefficiencies are acknowledged—and accepted—as part of a much larger strategic framework.

Defense Spending and Arms Races

National interest also shapes defense budgets, often at the expense of economic priorities.

During the Cold War, both the United States and the Soviet Union pursued military superiority through aggressive arms races.

The U.S. allocated vast sums to advanced weapons development, NATO commitments, and overseas military deployments, all in the name of containing communism.

These commitments required enormous fiscal resources—resources that might otherwise have funded domestic programs, infrastructure, or social services.

The Soviet Union’s path mirrored this approach, but with greater economic consequences.

Its unwavering focus on military buildup placed tremendous strain on an already fragile economy and was a contributing factor in its eventual collapse in the early 1990s. In both cases, the arms race was seen not as discretionary, but essential—a matter of ideological and strategic survival, regardless of the economic toll.

Protectionism and Agricultural Policies

Agriculture is another domain where national interest frequently overrides global trade norms and economic efficiency.

India’s agricultural policies provide a clear example. In an effort to shield its vast rural population—which represents a significant segment of the national workforce—India has maintained high tariffs on imported agricultural goods and extended subsidies to domestic farmers.

These protectionist measures have drawn criticism for distorting international markets and fostering inefficiencies. India’s resistance to liberalizing its agricultural sector has triggered disputes at the World Trade Organization.

Yet for Indian policymakers, the calculus centers on rural stability and the prevention of large-scale social unrest.

In this context, agriculture is not merely an economic sector—it is a core pillar of cultural identity and political continuity.

National Interest in Energy Security

Energy policy is often shaped as much by national sentiment as by price or supply dynamics.

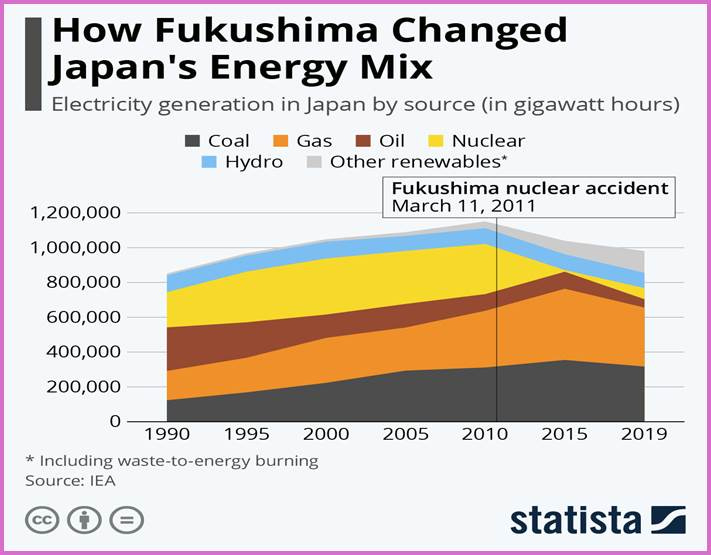

Japan’s post-Fukushima energy shift is a powerful demonstration of this. Following the 2011 nuclear disaster, Japan made the decision to shut down most of its nuclear reactors—despite the fact that nuclear power had supplied a substantial share of the country’s electricity.

In the wake of that decision, Japan ramped up imports of fossil fuels, particularly liquefied natural gas (LNG), at far greater expense. This move not only increased Japan’s energy costs but also had negative environmental implications.

Even so, the choice reflected a broader national priority: restoring public trust, ensuring safety, and addressing widespread public opposition to nuclear energy. In that moment, economic efficiency took a back seat to societal cohesion.

Summary

Taken together, these examples illustrate the deeply intertwined relationship between national and economic interests.

While economic rationality often guides policy, there are critical junctures where strategic imperatives—sovereignty, security, cultural preservation, or geopolitical influence—take the lead.

These decisions reflect a broader conception of national well-being, one that extends beyond short-term financial metrics to encompass long-term strategic vision and domestic stability.

The trade-offs involved are rarely clean or easy, but they underscore an essential truth of statecraft: in times of pressure, economic costs are often willingly borne in pursuit of goals deemed too important to ignore.

Case Studies in National Interest

The Middle East Following World War II

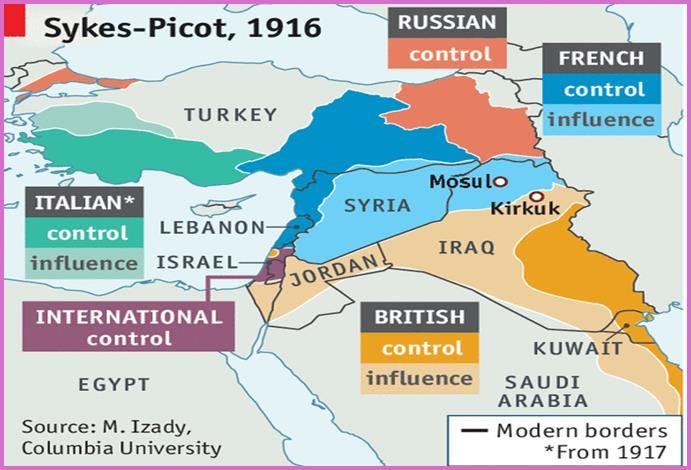

The redrawing of the Middle East map by the Allied powers after World War II stands as a stark example of national interest overshadowing cultural and regional considerations.

This process—driven by the colonial ambitions and strategic objectives of Britain, France, and later the United States—was crafted to serve economic, political, and military goals rather than the interests or well-being of the diverse populations that inhabited the region.

The consequences of these decisions still reverberate today, contributing to enduring instability, conflict, and unresolved grievances across the Middle East.

Geopolitical and Economic Priorities

The division of the Middle East was profoundly shaped by the Allied powers’ desire to secure access to the region's vast oil resources, which had become increasingly critical to industrial economies and military operations.

Britain prioritized control over areas like Iraq—home to significant oil reserves—and sought dominance over trade routes such as the Suez Canal.

France, meanwhile, moved to solidify its influence in territories like Syria and Lebanon to reinforce its colonial footprint.

These objectives were codified in early agreements like the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916, which, though predating World War II, laid the groundwork for postwar territorial arrangements.

The creation of new states such as Iraq and Jordan was often based more on strategic convenience than cultural or historical logic.

Iraq, for instance, was formed by combining three former Ottoman provinces—Basra, Baghdad, and Mosul—each home to distinct ethnic and religious communities, including Sunni Arabs, Shia Arabs, and Kurds.

This artificial amalgamation served British interests by creating a state more easily influenced from abroad, but it also sowed deep divisions.

These groups had little shared history and longstanding grievances, setting the stage for a cycle of internal conflict and instability that persists to this day.

Cultural and Regional Disregard

In prioritizing strategic outcomes, the Allied powers largely ignored the complex social fabric of the Middle East.

Ethnic, religious, and tribal affiliations—long central to governance and identity in the region—were brushed aside in favor of borders drawn by foreign rulers in distant European capitals.

This disregard for local dynamics led to the creation of states where minorities often dominated majorities, or vice versa, fostering decades of unrest and marginalization.

One of the most prominent examples is the Kurdish people—among the world’s largest stateless ethnic groups.

Despite assurances made in the Treaty of Sèvres (1920), the Kurds were denied a nation-state. Their homeland was carved up and distributed among Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria.

The decision was less about justice or self-determination and more about appeasing Turkey, which the Allies sought to stabilize as a bulwark against Soviet influence.

Strategic Imperatives in the Early Cold War

The onset of the Cold War further cemented the dominance of national interest over regional autonomy in the Middle East. With its strategic location straddling Europe, Asia, and Africa—and its abundance of oil—the region became a key arena for competition between Western powers and the Soviet Union.

In pursuit of geopolitical advantage, the Allies sought to install and support regimes that would remain aligned with the West, even when doing so meant backing authoritarian governments or unpopular monarchies.

A defining example was the Anglo-American coup in Iran in 1953, which deposed the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh after he nationalized the country’s oil industry. Fearing a shift toward Soviet alignment, Western powers restored the Shah to the throne, securing continued access to Iranian oil.

While this satisfied short-term strategic goals, it crushed Iran’s democratic momentum and fueled resentment that ultimately culminated in the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

Long-Term Consequences

The Allied redrawing of the Middle East map, rooted in national self-interest, has left a legacy of instability that continues to define the region.

The imposition of artificial borders and the preference for strategic alignment over cultural coherence created fragile states plagued by internal divisions, authoritarianism, and recurring conflict. Civil wars, insurgencies, and sectarian violence in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon can often be traced directly back to these postwar decisions.

This legacy has also contributed to the rise of anti-Western sentiment. Many in the region view the actions of the Allied powers as imperialist exploitation, feeding a narrative of betrayal and dominance. Extremist movements have capitalized on these historical grievances, using them to recruit followers and justify violence.

In sum, the Allied powers’ decisions to prioritize geopolitical control and economic access over cultural and regional realities in the post–World War II Middle East illustrate the deep and lasting consequences that can result when national interest is elevated above all else.

Colonial and Mercantilist Policies

During the mercantilist era from the 16th to 18th centuries, European powers like Britain, France, and Spain structured their economies to concentrate wealth through protectionist policies.

The British Navigation Acts (1651–1849), for example, mandated that trade with Britain and its colonies be conducted exclusively on British ships. While this restricted trade efficiency, it bolstered Britain’s merchant marine and strengthened naval power—key pillars of its global empire.

In France, Jean-Baptiste Colbert promoted similar policies through a system known as Colbertism. By imposing high import duties on foreign goods—particularly textiles and luxury items—France aimed to shield domestic producers and achieve economic self-sufficiency.

Although these tariffs increased the cost of goods at home, they were justified as necessary to reinforce France’s economic independence and diminish reliance on foreign imports.

Trade Wars and Tariffs

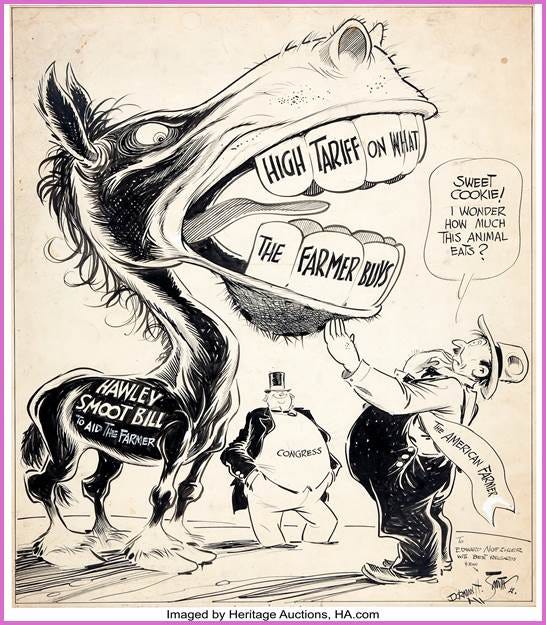

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 remains one of the most infamous episodes of modern protectionism.

Enacted during the Great Depression, it raised tariffs on over 20,000 imported goods in an effort to shield American farmers and manufacturers from foreign competition. The result was a cascade of retaliatory tariffs from other countries, deepening the global economic downturn. Still, the policy reflected a political imperative: protect domestic industries at all costs.

Fast forward to 2018, when the U.S. launched a trade war with China under the Trump administration.

Tariffs were imposed on steel, aluminum, and a wide array of consumer goods, motivated by concerns over intellectual property theft, trade imbalances, and national security. These tariffs disrupted supply chains and drove up costs for American consumers and businesses. Nonetheless, they were publicly defended as necessary measures to protect U.S. interests and rectify long-standing trade grievances.

This remains a looming issue for the Second Trump Administration, which continues to target China. Yet in doing so, it risks pulling Canada and Mexico into the crossfire—two countries increasingly used as intermediaries for Chinese exports into the U.S.

Industrial Protectionism

The argument for shielding "infant industries" has long been invoked by nations looking to nurture their domestic industrial bases.

In the 19th century, the United States imposed protective tariffs to foster its manufacturing sector, echoing the vision laid out by Alexander Hamilton. These measures were designed to insulate American producers from established British competitors.

Germany followed a similar path under Otto von Bismarck in the late 1800s, using tariffs to protect fledgling industries and reduce reliance on imports. This strategy helped pave the way for Germany’s eventual industrial dominance.

In the mid-20th century, newly independent countries like India and Brazil adopted import substitution industrialization (ISI) policies.

India, for instance, imposed steep tariffs on imports and restricted foreign investment to build domestic capacity and achieve self-reliance.

Though often accompanied by inefficiencies and slower growth, these policies were viewed as vital for escaping post-colonial economic dependence.

Agricultural Protectionism

Agriculture is a sector where national interest routinely overrides market logic.

The European Union’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), launched in the 1960s, provides subsidies to farmers and erects tariffs against foreign agricultural products. While the policy distorts international markets and leads to periodic overproduction, it reflects the EU’s long-standing commitment to food security and rural livelihoods.

In the United States, agricultural protectionism is a deeply entrenched feature of federal policy.

Through instruments like the Farm Bill, the U.S. government provides direct payments, crop insurance, and price supports to domestic farmers.

These measures have helped shield U.S. agriculture from global competition, even as they provoke trade disputes and draw criticism for undercutting producers in developing nations.

For example, cotton subsidies have been blamed for harming farmers in countries like Mali and Burkina Faso—but they persist due to the political importance of rural constituencies.

Energy and Resource Protection

Energy security represents another area where national interest routinely overrides economic efficiency.

During the 1973 Oil Embargo, Arab nations halted oil exports to the U.S. and its allies in response to support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War. The result was a global energy crisis that rocked economies worldwide. But from the perspective of OPEC, it was a calculated political move.

While it cost them revenue in the short term, it elevated their regional power through the weaponization of a critical resource.

Today, protectionist policies also extend to strategic materials.

China, which dominates the global supply of rare earth elements essential to high-tech manufacturing, has restricted their export to maintain a geopolitical and technological edge.

In doing so, China has prioritized long-term strategic positioning over near-term economic benefits from trade.

Geopolitical and Military Decisions

Military investments often reveal the clearest tensions between national interest and economic cost.

During the Cold War, both the United States and the Soviet Union devoted vast resources to military expansion and nuclear development.

For the U.S., heavy investments in NATO and global defense commitments placed pressure on domestic finances—but were considered essential to counter Soviet influence.

The Soviet Union’s emphasis on heavy industry and armaments, especially under its Five-Year Plans, weakened its consumer economy but supported its aspiration to remain a global superpower.

Japan offers a postwar example of industrial policy shaped by national interest. In the decades following World War II, the Japanese government heavily subsidized its automobile and electronics sectors.

Although these measures drew criticism and occasionally triggered trade tensions, they played a pivotal role in establishing Japan as a global technology leader.

Cultural and Sovereignty Concerns

Brexit offers another window into how national interest can overshadow economic logic.

Although EU membership provided Britain with clear economic advantages—chiefly access to a vast single market—the desire to regain control over immigration, legal frameworks, and trade policy proved decisive.

The resulting economic disruptions, including supply chain instability and diminished trade volumes, were seen by many as acceptable costs in the pursuit of restored sovereignty.

Japan’s response to the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011 underscores a similar prioritization of national sentiment.

By shutting down most of its nuclear reactors and shifting to more expensive fossil fuel imports, Japan placed safety and public trust above economic efficiency.

The move reflected a deep national trauma and a recalibration of risk—one rooted in collective memory, not market calculations.

Modern Resource Nationalism

Today, resource nationalism is rising as nations seek to protect critical materials needed for the energy transition.

Countries like Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo have enacted export restrictions on minerals like nickel and cobalt, essential for battery production and green technologies.

Though these measures reduce export revenues in the short term, they are justified by the goal of promoting domestic value-added industries and asserting control over strategic supply chains.

Summary

These case studies reveal how national interest and protectionism consistently assert themselves over economic efficiency in pursuit of broader strategic goals.

Whether driven by security, sovereignty, cultural preservation, or geopolitical advantage, these decisions often carry steep economic costs.

But they endure because they reflect enduring political realities—realities that rarely fit within the tidy logic of globalization.

These shifts bring about higher costs, reduced efficiencies, strained geopolitical relationships, and elevated uncertainty.

So how exactly does the Second Trump Administration plan to navigate this fragmented terrain—and what will it cost to impose control on chaos?

This post continues below for FOUNDER-level subscribers.

Upgrade to FOUNDER to get full access to in-depth analysis, investment implications, and forward-looking risk assessments.

![apushcanvas [licensed for non-commercial use only] / The Arab Oil Boycott apushcanvas [licensed for non-commercial use only] / The Arab Oil Boycott](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!oO7u!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0bd469a8-4bd6-4ab1-9c43-546595680865_676x404.jpeg)